“Far apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, individuals cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and reinvention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other”.

‒Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed

The adaption of constructivist practices and digital tools into K-12 learning is pragmatic because constructivism can fill voids resulting from an over emphasis on performance and grades over learning. The ideal that the tenets and methodologies of DH and ITP can enhance K-12 learning stems from their inclusive and collaborative values that are needed to support students’ ventures into learning coding languages where technological tools could advance research processes, or through making and building processes that can provide valuable insights into how things work, which posits a creative ethos to replace stagnant punitive methodologies in their classrooms. My advocacy for the reframing of K-12 pedagogies stems from concerns that students who have grown detached from learning should have access to needed resources and mentoring that are essential to invigorating their interests in learning. For instance, students could become compelled to pursue historical knowledge if they were to experience living conditions, politics and cultures that are different from their norms as is possible through online gaming. One such website, Mission US https://ashp.cuny.edu/mission-us “is an adventure-style online game that provides learning opportunities for standard-aligned social history content that are supported by classroom activities and primary texts” (Mission US | ASHP/CML). Mission US demonstrates how game based learning can provide quality learning experiences to students who take on game based identities so that their learning is contextualized in the social, cultural and political ideologies critical to the experience, which engenders deeper understanding and knowledge of histories through digital means. Technologies aid educational experiences because they are fluid throughout systems and societies. According to Professor Steven E. Jones “technology is not simply a thing that is separate and apart from human reality, but rather networked data is everywhere” (Steven E. Jones 1). The ideal that networked data is in and throughout our world assumes its uses for exploration and experimentation by K-12 students in learning, so that technologies, the internet, and digital media have the potential to differentiate student learning from narrow and punitive methodologies to expansive constructs that support interdisciplinary learning and experimentation. Reinvigorating K-12 learning with 21st century toolsets should require an articulated view of expectations for student learning that could be drawn from the DH community particularly because K-12 students are currently experiencing methodologies that are closed and non-public which is opposite the “public pedagogies of DH practices” (Gold 16). Understanding that students will likely carry forward values experienced in their younger years into their adult worlds is essential to framing their ongoing educational development. In her writing This is Why We Fight: Defining the Values of the Digital Humanities, Lisa Spiro, the Executive Director of Digital Scholarship Services at Rice University’s Fondren Library described the importance of creating core values that are relatable to the DH community. Even though Spiro formed these values in relation to the under-graduate and graduate levels, I argue that they are well suited for K-12 learning as “openness and collaboration” (Gold 16) should undergird normal classroom interactions. Creating a framework in which K-12 students could build social learning skillsets that are inclusive of collaboration into their everyday experiences posits the importance of their guidance into skillsets that require “critical thinking, inquiry, debate, pluralism, and a balance of innovation and tradition, and exploration and critique” (Gold 19) which can be developed through pedagogies that support student to student and student to teacher interactions (Ladson-Billings 318).

It is my view that constructivism can provide many opportunities for students to rediscover how their curiosity can deepen study based on course curriculum, situated in usages of technologies that can lead to the development of material works that are manifestations of their thought streams. For instance, CRP can bring students into rich discussions that become the basis for projects that evince their interests and understanding, so that this approach to learning has the potential to resonate with students as it essentially alleviates classroom tensions caused by drilling methodologies, by adding qualitative constructs through social Socratic learning. DH and ITP are well developed practices that are fully rooted in pedagogies that can guide K-12 educators out of restrictive practices, and it is for this reason that I believe they are well situated to train and certify K-12 educators in praxis that can revitalize learning. Educator Alex Reid observed that digital humanists “are not focused on the impact of technology on the contemporary human condition as they could be, so that literacy, pedagogy and contemporary media are being ceded to other non-humanistic or quasi-humanistic fields” (Gold 342), which is concerning as policy makers at the K-12 level exclude educators in decision making directly effecting qualitative experiences. Although there is a tendency for digital humanist to favor “software writing, indexing and data mining” (Gold 342), they have fostered attention to the needs of undergraduate study in the past through such initiatives as Writing Across the Curriculum (“WAC”) “which provided remedial instruction in math and writing during the open admissions initiative” (Gold 393). WAC engendered Blogs@Baruch, “an online publishing and academic networking platform that utilizes technology through the sharing of student writing and content” (Gold 394), and the American Social History Project, (“ASHP”) which was founded by Stephen Brier and Herbert Gutman, constructed the digitization of histories “to improve teaching through the use of primary source documents and visual materials” (Gold 394), so that its fostering of the Who Built America (“WBA”) initiative also offers historical renderings in the form of digitized cd-roms (Mission US is a component of the WBA series). These technologies based initiatives serve as examples of how digital humanist can contribute to deepening students’ interests through the sharing of content, that can help students discover, develop and demonstrate their social and cultural interests.

DH and ITP have evinced how “technology can open new possibilities and contexts for teaching and learning” (Gold 340), so that K-12 students are utilizing digital technologies to describe their concerns and interests, demonstrating an adeptness in applications and multimedia. Given advances in technologies and languages, the possibility that students’ digital skillsets could be developed to include research utilizing digitized corpuses, posit opportunities to broaden and enhance their understanding of cultural and social issues, particularly when new learning is contextualized to prior knowledge. According to educator Carol Lee, “computer and non-computer based learning technologies must be contextualized through students’ cultural models and prior knowledge” (Lee 46) if they are to invoke new learning when needed. Lee argues against a “default hypothesis that underachieving black and brown students and those who are impoverished are not adequately resourced for learning disciplinary knowledge” (Lee 46). These uses of varying technologies can detangle the effects of poverty, under-resourced and segregated schools, and restrictive methodologies that must be undertaken if lower socioeconomic and minority students are to gain critical skillsets needed to be viable. In this regard, pedagogies that are enriched by DH and ITP practices can reframe how K-12 students’ educations are developed, particularly when they are constructed to affirm the right to literacy and educational equity.

According to Tom Liam, Column Editor for the National Council of Teachers of English, under CCSS reading has morphed into an “reading for informational text” (Lynch 111), exercise that has a profound effect on how texts are experienced because when students are not reading for content, they are not connecting with text in ways that lead to reflection, or as Rosenblatt described, are missing those rich moments when “meaning happens during the interplay between text and a reader” (Rosenblatt x). This issue has become very concerning to individuals who advocate for the skill of reading for enrichment as essayist, novelist and editor Alberto Manguel, posit that “knowledge lies not in the accumulation of texts or information, nor in the object of the book itself, but in the experience rescued from the page and transformed again into experience, in the words reflected both in the outside world and in the reader’s own being” (Lynch 111), so that encouraging and guiding students to be more fully engaged with content, is a crucial aspect of their development. The importance of students’ ability to connect with texts, cannot be overstated because it is within the realm of content that curiosity, inspiration, and reflection are borne and satisfied. The argument for supporting critical thinking as a flexible and unrestricted activity must be accompanied with readily available access to content, essentially through digital means. Liam advances an argument “that technology as software is relevant for students’ work, as it is pronounced through and within our world so that the notion that software should support students as readers” (Lynch 112) takes on salience when we consider the need for improved reading and writing skills that should be borne and developed during the K-12 experience. Liam provides the following arguments as a basis for advocacy of DH in K-12 classrooms:

“Critical awareness and use of software that is powered by language is paramount if students are to masters its usages for creative and productive ends;

K-12 DH can reestablish the teaching of English as the dominant qualitative course of study over STEM, reasserting its prominence as an indispensable content area;

Introducing DH in K-12 classrooms prepares students for future study using technology and digital tools; and

Teaching programming languages alongside human languages allows students to engage rigorously and comparatively with notions of syntax, grammar structure, and even audience or authorial effect” (Lynch 112).

The undertaking of DH project oriented work can become topically oriented amongst varying humanistic fields. Mark Sample, Associate Professor of Digital Studies at Davidson College offers insight on the work of a digital humanities center which he posits “may have its focus on pedagogy, building things, research, coding or media studies, describing the potential for disciplines to converge with the digital humanities” (Gold 282–283). DH and ITP have the potential to cause an upswing in the ethos of K-12 classrooms as students’ educational experiences are reified through creative experimentation that reflects an understanding of interdisciplinary topics that have to bear on their social and cultural interests. This matters as the affordances to K-12 students of digital technologies and tool can situate their continued growth of knowledge by undertaking increasingly more involved and challenging explorative projects, through their development as readers, writers, and experimentalists.

The use of digital tools and technologies can assist students in developing writing skills that are needed to advance their studies, such that students’ essentially benefit from access to various digital tools, to improve their writing skills. Writing Buddy (“WB”) is one such digital gaming tool that is currently being developed to provide a “digital writing partner through game play in a challenging puzzle based writing environment” (Samuel et al. 1). Through WB students can construct characters and move game specific narratives forward through solving puzzles through player created stories” (Samuel et al. 389), as they envision what act a character might take, or how a narrative might evolve based on some past action. If students decide to change the direction of the game, then WB may force students to revise past actions. In this way, WB situates student writing as a crucial aspect of gameplay which must be developed if they are to take on new challenges. When WB is fully developed, this tool has the potential to help students develop their writing skills and can help students cultivate continued interests in writing. There are many ways that technologies can help develop students’ educational experiences that are essential for achievement and continued academic growth, which could posit dramatic changes in student learning.

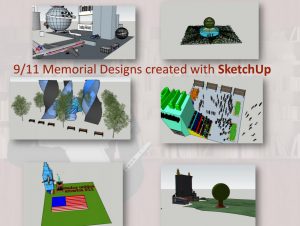

Fig. 3 Remembering and Rebuilding

PS 188 The Island School in Manhattan’s District 1 has introduced constructivist pedagogical practices into their classrooms via the use of multimodal digital tools, including for the creation of a 911 memorial, Remembering and Rebuilding http://schools.nyc.gov/NR/rdonlyres/BC5536BF-683A-4F64-8D9D-A957BED20967/0/01M188HO.pdf. This making and building project not only engaged students’ interest in discovering “what architecture is” (PS 188 The Island School 7) by assisting the transformation of their ideas into virtual and physical works but also created opportunities for students to explore digital environments and virtual modeling in the third dimension. The processes of working through digital mediums to construct the memorial exemplifly the potential for project oriented study to empower and aid students while solidifying their understanding of the event. In this instance, students’ exploration of digital processes was aided through their application of blogging, use of the 3d modeling software program SketchUp, and a 3D printer MakerBot that is supported through an open-source 3D printing program Replicator G. The construction of the virtual memorial required students to work within interdisciplinary subjects inclusive of “technology, geometry, architecture and social studies” (PS 188 The Island School), so that their work was situated out of collaborative and cooperative reliance of shared knowledge. The pedagogical approach to this study required specific lines of inquiry, including knowledge of the facts, surrounding the events of 9/11 and its impact on survivors and loved ones, so that students gained a broader understanding of why the event took place, and through their modeling activities, an understanding of the detriment of terrorist activities on lives and properties. Remembering and Rebuilding is an example of how divides in education caused by poverty can be neutralized so that the benefits of working through digital mediums cross socioeconomic barriers to learning by creating value streams which focused on writing skills as students used blogging as a platform to describe the events of 911. Louis Lahana, the “Techbarian” at PS 188 (PS 188 The Island School 1), extends students’ use of multimedia in their project based work to creatively form and express the cultural and social concerns of K-12 students. Although this paper does not presume to know the exact pedagogy that is utilized at P.S. 188, Lahana’s digital compilation of topics presents students with a wide range of choice subjects they could use to inform their study in pointing to the exercise of CRP. Lahana’s webpage (http://www.techbrarian.com/) invites students to take on challenges of humanistic relevance using semiotic materials to produce project based work so that as projects are formed, students are consistently engaged in writing exercises in preparation of blog posts, and video scripts. Similarly, in his work Multimedia as Composition Research, Writing and Creativity, Viet Thanh Nguyen, an Aerol Arnold Chair of English and American Studies, and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California, describes his pedagogical constructs of multimedia to conceptualize students’ storytelling about the Nation through the understanding of how multimedia could assist their creativity in relation to social and cultural issues. (Neuyen 4). Although his coursework was geared toward upper level study in academia, Nguyen refers to the use of multimedia as “a pedagogical strategy for both teachers and students that are tactics in the service of strategy” (Neuyen 4). Nguyen assessed current methodologies that form student learning to mirror that of their teachers as “utilitarian and rigid” in their processes, and argues that the use of multimedia supports student expression, especially for students who “think visually and audibly”. Lahana’s ongoing support of students’ project based work mirrors Nguyen’s belief that “shared learning occurs between teachers and students, as he posits that he learns from his students through his willingness to take risk related to working with new digital tools and in exploring social issues in which to produce project oriented work “https://vimeo.com/channels/socialaction/61523863.“

Lahana’s use of tech tools to facilitate students’ storytelling digitally, can also be applied to other forms of building and making projects that engage student learning in the context of culturally sustaining pedagogies. In Be Beautiful, Inside and Out https://vimeo.com/channels/socialaction/125414465, the effects of highly charged racial stigmas illustrate the personal effect of bias, demonstrating the result of stigmatization using video and semiotic materials. Students’ use of digital tools evinces the emotional impact of bullying that causes depression and anxiety and brings across how such stigmas can situate students as the outside other. Be Beautiful, Inside and Out also increases awareness of youth suicide so that this multimodal informational video frames a call to action and provides access to the NYC Youthline. Project oriented multimodal learning posits a shift from traditional print materials has the potential to become normative in K-12 classrooms as building and making are adopted into coursework. In another example of constructive learning, one student created a “Cigarette Smoke Detecting Shirt” that utilized a Lilypad[1] and smoke sensor device https://vimeo.com/channels/socialaction/176333648 where its functionality relies on code. Noted DH Humanist, Stephen Ramsay argued that “DH consists of building and making as much as it does coding” (Gold X), which matters as K-12 students may become future digital humanists with interests in computational study, as well as for their future careers and crafts that utilize many different digital tools and geospatial mapping technologies.

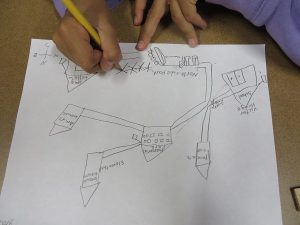

Fig. 4 Picture of Student at Walnut Elementary School

A precedent has been made for the use of geospatial tools within K-12 classrooms as students in grades 2 through 5 at Walnut Elementary School in Baldwin Park, CA learn how to think spatially, through the study of “land use, transportation, building footprints and aerial data and configure how to travel to the school or to the library,” using familiar landmarks to illustrate their maps and “calculate time travelled via walking or biking between points” (GISCorps – K-12 Project in California). These hand-drawn maps illustrate how young students perceive distance as they recall familiar objects in relation to each other so that in addition to perceiving time, space, and distance, their interests in working with maps can be developed using digital tools.

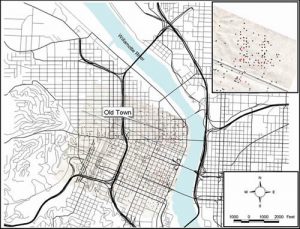

Fig. 5 Map of Lincoln High Project

Another instance of student learning via geospatial mapping occurred at Lincoln High School where students worked with Portland State University to “find trends in data concerning the Old Town History Project, combining multiple maps to illustrate illegal activities utilizing original arrest records, census data and city reverse directories” (Lincoln High Project) to construct the mapping project. The plurality of working with various information informs students’ interest across subjects as described by these maps. If these maps were being developed to establish causality or to define locations of continued illegal practice, their benefit to the user could visually describe why offenses occur especially when viewed through the lens of background information, including an awareness of how inappropriate behaviors could result out of impoverished, and segregated communities and a lack of centers of education that provide synergy in ethos that inspire student participation in learning.

There are many affordances that could be borne out of usages of technology in classrooms that extend beyond the multimodal or geospatial areas of digital toolsets. Yet, crucial to delivering these capabilities into classrooms necessitates that educators “develop their pedagogical content knowledge” (Van Driel and Berry 26) (PCK) if they are to “adapt their pedagogies into a flexible understanding to the benefit and enhancement of student learning in a variety of ways” (Van Driel and Berry 27). One critical issue that educators must be able to bridge in experimentation is that of failure, which DH values as a “useful result” (Gold 29) because through reflection failure provides a means for the continued construction of knowledge. Building collaborative ethos’ of deep learning in schools who have previously experienced narrowed curriculum instruction, is necessary so that students see their schools as trust oriented centers that support their interests, guided by educators who construct new learning under the direction of DH and ITP.

Without new approaches to learning that utilize multimodal digital toolsets and technologies that are embedded in and throughout societies, whole communities will be relegated as unprepared to thrive, where new technological constructs demand literate practices. Therefore, it is “critical to understand the uses of software and its languages to be viably connected to technologies creative and productive ends” (Lynch 112). I advocate for the study of multimodal digital and computational tools throughout the K-12 school experience for several reasons, namely because these toolsets together with constructivist pedagogies can help students express their social and cultural interests, and because they are the means in which punitive methodologies can be replaced with pedagogies that afford continued learning and growth that will ensure literacy and educational equity.

[1] Lilypad is an Arduino main board product that is programmed using Arduino software.